Editor’s note: This content was originally published for the Christian Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Event. This content is shared with Denver Institute for Faith & Work with consent from CEF. Aimee Minnich was a speaker at "Business for the Common Good" on Friday, Jan. 31, 2020.

As faith-driven impact investing grows, so too does theconfusion about how much financial return an investor should expect. One womanwho heads a faith-based family foundation explained: “As impact investors wewill not accept less than market-rate financial returns. We aim to beat everybenchmark. Less than that and we should just fold up and go home.” Anythingless than stellar financial returns signals weak fundamentals, so the thinkinggoes.

Others believe their role as stewards of large endowmentscarries the responsibility to back projects with high social and spiritualimpact that cannot offer the promise of high financial return. By supportingthese projects early with capital and expertise, these investors expect tode-risk the project and make it attractive to subsequent investors.

For those new to impact investing, these strongly-held butcontradictory opinions can leave one confused. This paper will untangle theconfusion and propose a balanced approach with room for investments across abroad spectrum of risk/financial return/impact.

Roots of the Confusion

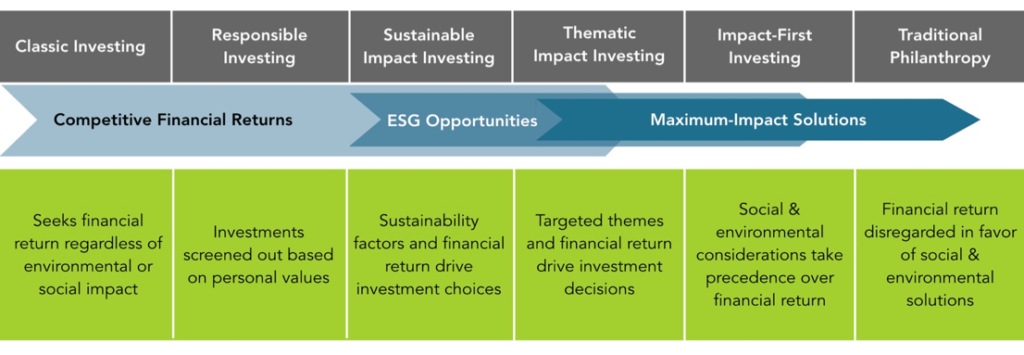

“Impact investing”—a term coined in 2006 by Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, and other pioneers—means intentionally placing capital in companies, organizations, and funds with the goal of generating a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return. Knowing that the real money wouldn’t be attracted to the space without the promise of market-rate returns, these early pioneers set about to prove that it is possible to beat the benchmarks through impact investing.

And it is working. Early data on financial returns from impact investing suggests there is no compromise on monetary gain for investors when achieving measurable social impact.1 The findings have led to a prevailing sentiment that serious investors should never accept less than market-rate financial return.

The roots of the “always beat the market” approach to impact investing stem from a view of the world that is binary. Someone can either make a 0% investment in a charity and call it a grant or make an investment with market-rate returns. Early pioneers in this space perpetuate this idea with charts describing impact investments on a sliding scale between high-impact/low financial return and low-impact/high financial return. 2

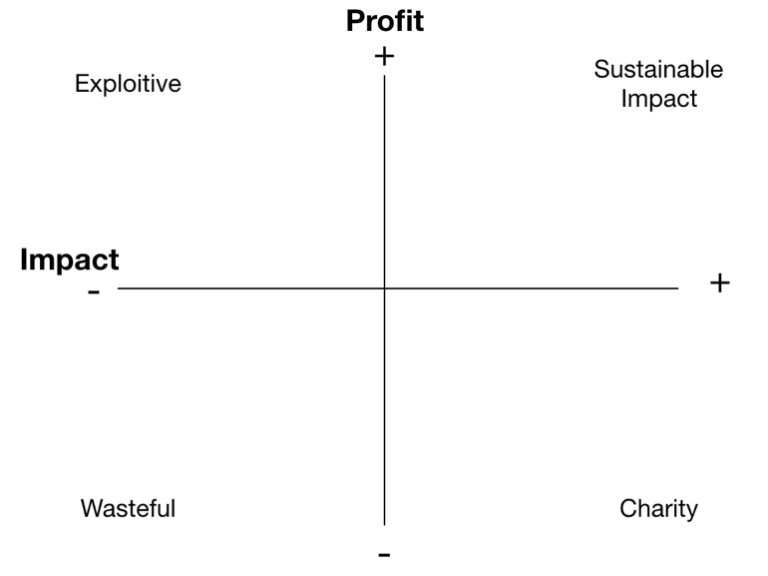

A one-dimensional view like this does not allow us to evaluate investments with similar financial performance but different impact outcomes. For example, how would we evaluate a 15% APR loan to a company that employs six women freed from sex trafficking in Thailand versus a 15% APR loan to manufacturing company employing 35 people in an unreached village of Northern India? A more holistic way to visually represent the impact investing spectrum is to illustrate the interaction between profit and social outcomes on a simple X-Y axis.

Exploitive. Where profit is high and the company is harmful to the environment, employees, and/or the community, we call it exploitive. Organized crime syndicates, drug deals, and blood diamonds provide examples in the far upper left.

Wasteful. Operations with no profit and negative impact fall in the bottom left corner as wasteful. At the risk of provoking an argument, there may be a failed government program or two that fall into this quadrant.

Charity. Organizations that provide great social/spiritual/environmental impact without profit are considered charity. Without donations, they would not be sustainable. Certainly, these programs are worth supporting with our grant funding, but they would not be considered impact investing.

Sustainable impact. This happens when financial operations are profitable, and the social/spiritual/environmental impact is positive.

Every organization, from the simplest nonprofit to the largest multi-national conglomerate, can be assigned a place on the chart. Financial return and impact are measurable and vary over time. Even so, we need more robust measurement frameworks and tools to help companies and investors best understand social, and especially spiritual, impact.

Our Best Investments May Not Always be “Up & to the Right”

Our natural tendency as investors and business leaders it to aim for continued growth up and to the right—toward highest financial return and highest impact. However, that may not always be possible or appropriate. Scripture implores a more holistic, portfolio approach to deploying capital.

Money and possessions are addressed more than 800 times from Genesis to Revelation. When we view these passages with an eye to understanding investments, a few patterns emerge. The Bible commends the following uses of financial resources:

1.Direct aid, also called charity: The Good Samaritan (notice this was given in response to a crisis)

2. Gifts to support the temple and priests: Deuteronomy 14

3. Market-rate financial return: Parable of the Talents

4. Gleaning: Leviticus 19 and the Book of Ruth

Charity, tithes, and market-rate investments are easy to understand but let’s consider gleaning a bit further. Leviticus commanded landowners to leave a little fruit on the vine or grain on the stalk and allow the poor and needy to come behind one’s own workers to pick the leftovers. In that way, those experiencing financial difficulties could work and acquire basic sustenance for their family. The Theology of Work Project explains well the difference between gleaning and charity:

“In charity, people voluntarily give to others who are in need. This is a good and noble thing to do, but it is not what Leviticus is talking about. Gleaning is a process in which landowners have an obligation to provide poor and marginalized people access to the means of production (in Leviticus, the land) and to work it themselves. Unlike charity, it does not depend on the generosity of landowners. In this sense, it was much more like a tax than a charitable contribution. Also, unlike charity, it was not given to the poor as a transfer payment. Through gleaning, the poor earned their living the same way as the landowners did, by working the fields with their own labors. It was simply a command that everyone had a right to access the means of provision created by God.”3

Modern examples of gleaning include leaving an above-average

tip or allowing a bellhop to carry bags to the room so they can earn a tip. Applying

this command to the realm of investing reveals a bullseye larger than just the

far corner of the top, right quadrant.

At the top of the oval, companies with strong financial return sometimes do not provide social/spiritual benefit as strong as a charity but are worthy of impact investing capital. Their profits can fuel further giving for investors.

On the other end of the financial return spectrum, donor/investors may choose to take a lower financial return if the expected impact is high. For example, a friend of ours lent money to an apple farm in Ethiopia at 4% interest. A risky investment like this with an interest rate well below market might looks foolish to those who believe impact investments should always beat the market. But our friend understands that providing jobs in marginalized and impoverished communities requires sacrificing some personal financial gain. He is practicing the biblical concept of gleaning as applied to investments.

Some people fear that accepting less financial return signals they are being taken advantage of or that they’re allowing a business owner to run with weak fundamentals. That is certainly a valid concern, but that is not what gleaning entails. In ancient times, following the commandment to leave room for strangers harvesting at the edges of one’s fields meant that a landowner had to be an even better farmer to make sure there was enough to feed his family. He also had to depend on God’s provision.

Likewise, today’s investors and business owners must adhere to strong fundamentals. Government instability, systemic graft, decades of war, famine, lack of access to education— the social and political climate in much of the developing world means that solving global poverty requires excellence. “Investment gleaning” simply allows some of one’s personal financial return to help level the playing field for the poor and marginalized.

How to Tell the Difference Between Gleaning and Waste

God designed His economy to run on the fuel of generosity. We never desire to replace charitable giving, but adding impact investments can be a perfect complement to a philanthropic portfolio. Imagine the good that can be accomplished to end sex trafficking, create jobs, provide clean water, and share the Good News when we unleash even more assets for Kingdom work. With such a tremendous opportunity, it is worth the effort to learn how to discern the difference between worthwhile gleaning investments and ones we should avoid.

At Impact Foundation we have developed a rating system to help us evaluate potential investments. It is outside the scope of this paper to delve fully into investment vetting, but a few questions can help begin the discernment process:

1.Impact - What impact is the company seeking? Is there a written plan for achieving positive social and spiritual outcomes? Has the company developed measurement systems for understanding its impact?

2.Reason for Lower Returns - What is the reason given for why the company is offering below-market returns? Is it because costs for training disenfranchised workers is high? Is it because operating in an underdeveloped market are higher? If the company’s leaders cannot articulate a valid reason, that may signal an investment to avoid.

3.Ownership - What is the ownership structure? Who owns the company? When will the owners begin earning payouts? It is a good sign if local leadership owns the company. If owners are not members of the group your investment is intended to benefit, then pay close attention to when and how owners will profit. The goal is to avoid investments where much of the financial return that investors sacrifice benefits private individuals.

There is much more that could be said on the subject, but we will close with an example of the good that be accomplished through investment gleaning.

Gleaning in Action: Magic City Woodworks

Magic City Woodworks, a charity with an earned-revenue model, helps young men in inner city Birmingham bridge the gap between idleness and meaningful work. They offer a one-year paid apprenticeship that trains men to be teachable, to gain character, and to gain skills that will serve them in future employment. While product sales are an important and growing component of Magic City Woodwork’s revenue, their mission to employ marginalized, unskilled young men means they will not be as profitable as a traditional furniture company. Donations and low-profit investments help protect the organization’s ability to focus on job and life training that is central to its mission.[